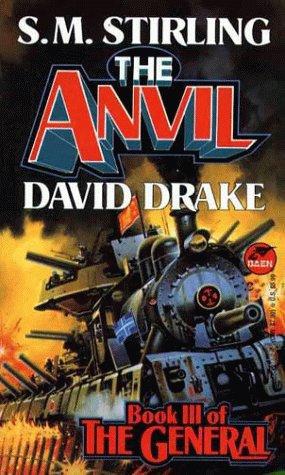

Книга: The Anvil

The Anvil

THE GENERAL

Book III

S.M. Stirling & David Drake

CONTENT

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter One

"Raj!" Thom Poplanich blurted.

Raj Whitehall's mouth quirked. "You sound more shocked this time," he said.

The way you look, I am more shocked, Thom thought, blinking and stretching a little. There was no physical need; his muscles didn't stiffen while Center held him in stasis. But the psychological satisfaction of movement was real enough, in its own way.

The silvered globe in which they stood didn't look different, and the reflection showed Thom himself unchanged — down to the shaving nick in his chin and the tear in his tweed trousers. A slight, olive-skinned young man in gentleman's hunting clothes, looking a little younger than his twenty-five years. He'd cut his chin before they set out to explore the vast tunnel-catacombs beneath the Governor's Palace in East Residence. The trousers had been torn by a ricocheting pistol-bullet, when the globe closed around them and Raj tried to shoot his way out. Everything was just as it had been when Raj and he first stumbled into the centrum of the being that called itself Sector Command and Control Unit AZ12-bl4-cOOO Mk. XIV

That had been years ago, now.

Raj was the one who'd changed, living in the outer — the real — world. That had been obvious on the first visit, two years after their parting. It was much more noticeable this time. They were of an age, but someone meeting them together for the first time would have thought Raj a decade older.

"How long?" Thom said. He was half-afraid of the answer.

"Another year and a half."

Thom's surprise was visible. He's aged that much in so little time? he thought. His friend was a tall man, 190 centimeters, broad-shouldered and narrow-hipped, with a swordsman's thick wrists. There were a few silver hairs in the bowl-cut black curls now, and his gray eyes held no youth at all.

"Well, I've seen the titanosauroid, since," Raj went on.

"Governor Barholm did send you to the Southern Territories?"

Raj nodded; they'd discussed that on the first visit. After Raj's victories against the Colony in the east, he was the natural choice.

"A hard campaign, from the way you look."

"No," Raj said, moistening his lips. "A little nerve-racking sometimes, but I wouldn't call it hard, exactly."

Observe, the computer said. The walls around them shivered. The perfect reflection dissolved in smoke, which scudded away —

— and returned as a ragged white pall spurting from the muzzles of volleying rifles. From behind a courtyard wall, Raj Whitehall and troopers wearing the red and orange neckscarves of the 5th Descott shot down an alleyway toward the docks of Port Murchison. Each pair of hands worked rhythmically on the lever, ting, and the spent brass shot backward, click, as they thumbed a new round into the breech and brought the lever back up, crack as they fired.

There were already windrows of bodies on the pavement: Squadron warriors killed before they knew they were at risk. Survivors crouched behind the corpses of their fellows and fired back desperately. Their clumsy flintlocks were slow to load, inaccurate even at this range; they had to expose themselves to reload, fumbling with powder horns and ramrods, falling back dead more often than not as the Descotter marksmen fired. A few threw the firearms aside with screams of frustrated rage, charging with their long single-edged swords whirling. By some freak one got as far as the wall, and a bayonet punched through his belly. The man fell backward off the steel, his mouth and eyes perfect O's of surprise.

A ball ricocheted from one of the pillars and grazed Raj's buttock before slapping into the small of the back of the officer beside him in the firing line. The stricken man dropped his revolver and pawed blindly at his wound, legs giving their final twitch. Raj shot carefully, standing in the regulation pistol-range position with one hand behind the back and letting the muzzle fell back before putting another round through the center of mass.

"Marcy!" the barbarians called in their Namerique dialect. Mercy! They threw down their weapons and began raising their hands. "Marcy, migo!" Mercy, friend!

Both men blinked as the vision faded — Raj to force memory away, Thom in surprise.

"You brought the Southern Territories back?" Thom said, slight awe in his voice. The Squadrones — the Squadron, under its Admiral — had ruled the Territories ever since they came roaring down out of the Base Area a century and a half ago and cut a swath across the Midworld Sea. The only previous Civil Government attempt to reconquer them had been a spectacular disaster.

Raj shrugged, then nodded: "I was in command of the Expeditionary Force, yes. But I couldn't have achieved anything without good troops — and the Spirit."

"Center isn't the Spirit of Man of the Stars, Raj. It's a Central Command and Control Unit from before the Collapse — the Fall, we call it now."

Neither of them needed another set of Center's holographic scenarios to remember what they had been shown. Earth — Bellevue, the computer always insisted — from the holy realm of Orbit, swinging like a blue-and-white shield against the stars. Points of thermonuclear fire expanding across cities . . . and the descent into savagery that followed. Which must have followed everywhere in the vast stellar realm the Federation once ruled, or men from the stars would have returned.

Raj shivered involuntarily. He had been terrified as a child, when the household priest told of the Fall. It was even more unnerving to see it played out before the mind's eye. Worse yet was the knowledge that Center had given him. The Fall was still happening. If Center's plan failed, it would go on until there was nothing left on Bellevue — anywhere in the human universe — but flint-knapping cannibal savages. Fifteen thousand years would pass before civilization rose again.

Thom went on: "Center's just a computer."

Raj nodded. Computers were holy, the agents of the Spirit, but Thom's stress on the word meant something different now. Different since he'd been locked in stasis down here, being shown everything Center knew. Nearly four years of continuous education.

"You know what you know, Thom," Raj said gently. "But I know what I know." He shook hi head. "We slaughtered the whole Squadron," he went on. Literally. "Made them attack us, then shot the shit out of them."

"And how did Governor Barholm react?" Thom asked dryly. By rights, Thom Poplanich should have been Seated on the Chair; his grandfather had been. Barholm Clerett's uncle had been Commander of Residence Area Forces when the last Governor died, however, which had turned out to be much more important.

"Well, he was certainly pleased to get the Southern Territories back," Raj said, looking aside. That was hard to do inside the perfectly reflective sphere. The expedition more than paid for itself, too — and that's not counting the tax revenues."

Observe, Center said.

— and men in the black uniforms of the Gubernatorial Guard were marching Raj away, while the leveled rifles of more kept Suzette Whitehall and Raj's men stock-still —

— and Raj stood in a prisoner's breechclout and chains before a tribunal of three judges in ceremonial jumpsuits and bubble helmets —

— and he sat bound to an iron chair, as the glowing rods came closer and closer to his eyes —

Raj sighed. "That might have happened, yes. According to Center, and I don't doubt it myself. I was a little . . . apprehensive . . . about something like that. I'm not any more; the Army grapevine has been pretty conclusive. In fact, when the Levee is held this afternoon, I'm confident of getting another major command."

"The Western Territories?'

"How did you guess?"

"Even Barholm isn't crazy enough to try conquering the Colony. Yet."

"Yes." Raj nodded and ran a hand through his hair. "The problem is, he's probably too suspicious to give me enough men to actually do it."

Thom blinked again. Raj has changed, he thought. The young man he had known had been ambitious — dreaming of beating back a major raid from the Colony, say, out on the eastern frontier. This weathered young-old commander was casually confident of overrunning the second most powerful realm on the Middle Sea, given adequate backing. The Brigade had held the Western Territories for nearly six hundred years. They were almost civilized . . . for barbarians. Odd to think that they were descendants of Federation troops stranded in the Base Area after the Fall.

"Barholm," Raj went on with clinical detachment — sounding almost like Center, for a moment — "thinks that either I'll fail—"

Observe, Center said.

Dead men gaped around a smashed cannon. The Starburst banner of the Civil Government of Holy Federation draped over some of the bodies, mercifully. Raj crawled forward, the stump of his left arm tattered and red, still dribbling blood despite the improvised tourniquet. His right just touched the grip of his revolver as the Brigade warrior reined in his riding dog and stood in the stirrups to jam the lance downward into his back. Again, and again . . .

"— or I'll succeed, and he can deal with me then." observe, Center said.

Raj Whitehall stood by the punchbowl at a reception; Thom Poplanich recognized the Upper Promenade of the palace by the tall windows and the checkerboard pavement of the terrace beyond. Brilliant gaslight shone on couples swirling below the chandeliers in the formal patters of court dance; on bright uniforms and decorations, on the ladies' gowns and jewelry. He could almost smell the scents of perfume and pomade and sweat. Off to one side the orchestra played, the soft rhythm of the steel drums cutting through the mellow brass of trumpets and the rattle of marachaz. Silence spread like a ripple through the crowd as the Gubernatorial Guard troopers clanked into the room. Their black-and-silver uniforms and nickel-plated breastplates shone, but the rifles in their hands were very functional. The officer leading them bowed stiffly before Raj.

"General Whitehall —" he began, holding up a letter sealed with the purple-and-gold of a Governor's Warrant.

"Barholm doesn't deserve to have a man like you serving him," Thom burst out.

"Oh, I agree," Raj said. For a moment his rueful grin made him seem boyish again, all but the eyes.

"Then stay here," Thom urged. "Center could hold you in stasis, like me, until long after Barholm is dust. And while we wait, we can be learning everything. All the knowledge in the human universe. Center's been teaching me things . . . things you couldn't imagine."

"The problem is, Thom, I'm serving the Spirit of Man of the Stars. Whose Viceregent on Earth —"

Bellevue, Center said.

"— Viceregent on Bellevue happens to be Barholm Clerett. Besides the fact that my wife and friends are waiting for me; and frankly, I wouldn't want my troops in anyone else's hands right now, either." He sighed. "Most of all . . . well, you always were a scholar, Thom. I'm a soldier; and the Spirit has called me to serve as a soldier. If I die, that goes with the profession. And all men die, in the end."

Essentially correct, Center noted, its machine-voice more somber than usual. Restoring interstellar civilization on Bellevue and to humanity in general is an aim worth more than any single life. A pause, more than any million lives.

Raj nodded. "And besides . . . in a year, I may die. Or Barholm may die. Or the dog may learn how to sing."

They made the embrhazo of close friends, touching each cheek. Thom froze again; Raj swallowed and looked away. He had seen many men die. Too many to count, over the last few years, and he saw them again in his dreams far more often than he wished. This frozen un-death disturbed him in a way the windrows of corpses after a battle did not. No breath, no heartbeat, the chill of a corpse — yet Thom lived. Lived, and did not age.

He stepped out of the doorway that appeared silently in the mirrored sphere, into the tunnel with its carpet of bones — the bones of those Center had rejected over the years as it waited for the man who would be its sword in the world.

Then again, he thought, stasis isn't so bad, when you consider the alternatives.

"Bloody hell," Major Ehwardo Poplanich said, sotto voce. "How long is this going to take? If I'd wanted to sit on my butt and be bored, I would have stayed home on the estate." He ran a hand over his thinning brown hair.

He was part of the reason that Raj Whitehall and his dozen Companions had plenty of space to themselves on the padded sofa-bench that ran down the side of the anteroom. Nobody at Court wanted to stand too close to a close relation of the last Poplanich Governor. Quite a few wondered why Poplanich was with Raj; Thom Poplanich had disappeared in Raj's company years before, and Thom's brother Des had died when Raj put down a bungled coup attempt against Governor Barholm.

Another part of the reason the courtiers avoided them was doubt about exactly how Raj stood with the Chair, of course.

The rest of it was the other Companions, the dozen or so close followers Raj had collected in his first campaign on the eastern frontier or in the Southern Territories. Many of the courtiers had spent their adult lives in the Palace, waiting in corridors like this. The Companions seemed part of the scene at first, in dress or walking-out uniforms like many of the men not in Court robes or religious vestments. Until you came closer and saw the scars, and the eyes.

"We'll wait as long as His Supremacy wants us to, Ehwardo," Colonel Gerrin Staenbridge said, swinging one elegantly booted foot over his knee. He looked to be exactly what he was: a stylish, handsome professional soldier from a noble family of moderate wealth, a man of wit and learning, and a merciless killer. "Consider yourself lucky to have an estate in a county that's boring; back home in Descott County —"

"— bandits come down the chimney once a week on Starday," Ehwardo finished. "Isn't that right, M'lewis?"

"I wouldna know, ser," the rat-faced little man said virtuously.

The Companions were unarmed, despite their dress uniforms — the Life Guard troopers at the doors and intervals along the corridor were fully equipped — but Raj suspected that the captain of the 5th Descott's Scout Troop had something up his sleeve.

Probably a wire garrote, he thought. M'lewis had enlisted one step ahead of the noose, having made Bufford Parish — the most lawless part of not-very-lawful Descott County — too hot for comfort. Raj had found his talents useful enough to warrant promotion to commissioned rank, after nearly flogging the man himself at their first meeting — a matter of a farmer's pig lifted as the troops went past. The Scout Troop was full of M'lewis's friends, relatives and neighbors; it was also known to the rest of the 5th as the Forty Thieves, not without reason.

Captain Bartin Foley looked up from sharpening the inner curve of the hook that had replaced his left hand His face had been boyishly pretty when Raj first saw him, four years before. Officially he'd been an aide to Gerrin Staenbridge, unofficially a boyfriend-in-residence. He'd had both hands, then, too.

"Why don't you?" he asked M'lewis. "Know about bandits coming down the chimney, that is."

Snaggled yellow teeth showed in a grin. "Ain't no sheep nor yet any cattle inna chimbley, ser," M'lewis answered in the rasping nasal accent of Descott "An' ridin' dogs, mostly they're inna stable. No use comin' down t'chimbly then, is there?"

The other Companions chuckled, then rose in a body. The crowd surged away from them, and split as Suzette Whitehall swept through.

Messa Suzette Emmenalle Forstin Hogor Wenqui Whitehall, Raj thought. Lady of Hillchapel. My wife.

Even now that thought brought a slight lurch of incredulous happiness below his breastbone. She was a small woman, barely up to his shoulder, but the force of the personality behind the slanted hazel-green eyes was like a jump into cool water on a hot day. Seventeen generations of East Residence nobility gave her slim body a greyhound grace, the tilt of her fine-featured olive face an unconscious arrogance. Over her own short black hair she was wearing a long blond court wig covered in a net of platinum and diamonds. More jewels sparkled on her bodice, on her fingers, on the gold-chain belt. Leggings of embroidered torofib silk made from the cocoons of burrowing insects in far-off Azania flashed enticingly through a fashionable split skirt of Kelden lace.

Raj took her hand and raised it to his lips; they stood for a moment looking at each other.

A metal-shod staff thumped the floor, and the tall bronze panels of the Audience Hall swung open. The gorgeously robed figure of the Janitor — the Court Usher — bowed and held out his staff, topped by the star symbol of the Civil Government.

Suzette took Raj's arm. The Companions fell in behind him, unconsciously forming a column of twos. The functionary's voice boomed out with trained precision through the gold-and-niello speaking trumpet:

"General the Honorable Messer Raj Ammenda Halgern da Luis Whitehall, Whitehall of Hillchapel, Hereditary Supervisor of Smythe Parish, Descott County! His Lady, Suzette Emmenalle —"

Raj ignored the noise, ignored the brilliantly-decked crowds who waited on either side of the carpeted central aisle, the smells of polished metal, sweet incense and sweat. As always, he felt a trace of annoyance at the constriction of the formal-dress uniform, the skin-tight crimson pants and gilt codpiece, the floor-length indigo tails of the coat and high epaulets and plumed silvered helmet. . . .

The Audience Hall was two hundred meters long and fifty high, its arched ceiling a mosaic showing the wheeling galaxy with the Spirit of Man rising head and shoulders behind it. The huge dark eyes were full of stars themselves, staring down into your soul.

Along the walls were automatons, dressed in the tight uniforms worn by Terran Federation soldiers twelve hundred years before. They whirred and clanked to attention, powered by hidden compressed-air conduits, bringing their archaic and quite nonfunctional battle lasers to salute. The Guard troopers along the aisle brought their entirely functional rifles up in the same gesture. They ignored the automatons, but some of the crowd who hadn't been long at Court flinched from the awesome technology and started uneasily when the arclights popped into blue-white radiance above each pointed stained-glass window.

The far end of the audience chamber was a hemisphere plated with burnished gold, lit via mirrors from hidden arcs. It glowed with a blinding aura, strobing slightly. The Chair itself stood four meters in the air on a pillar of fretted silver, the focus of light and mirrors and every eye in the giant room. The man enchaired upon it sat with hieratic stiffness, light breaking in metallized splendor from his robes, the bejeweled Keyboard and Stylus in his hands. From somewhere out of sight a chorus of voices chanted a hymn, inhumanly high and sweet, castrati belling out the chorus and young girls on the descant:

"He intercedes for us —

Viceregent of the Spirit of Man of the Stars!

By Him are we boosted to the Orbit of Fulfillment —

Supreme! Most Mighty Sovereign, Lord!

In His hands is the power of Holy Federation Church —

Ruler without equal! Sole rightful Autocrat!

He wields the Sword of Law and the Flail of Justice—

Most excellent of Excellencies! Father of the State!

Download His words and execute the Program, ye People —

Endfile! Endfile! Ennd . . . fiiille."

On either side of the arch framing the Chair were golden trees ten times taller than a man, with leaves so faithfully wrought that their edges curled and quivered in the slight breeze. Wisps of white-colored incense drifted through them from the censers swinging in the hands of attendant priests in stark white jumpsuit vestments, their shaven heads glittering with circuit diagrams. The branches of the trees glittered also, as birds carved from tourmaline and amethyst and lapis lazuli piped and sang. Their song rose to a high trilling as the pillar that supported the Chair sank toward the white marble steps; at the rear of the enclosure two full-scale statues of gorgosauroids rose to their three-meter height and roared as the seat of the Governor of the Civil Government sank home with a slight sigh of hydraulics. The semicircle of high ministers came out from behind their desks — each had a ceremonial viewscreen of strictly graded size — and sank down in the full prostration, linking their hands behind their heads. So did everyone in the Hall, except for the armed guards.

The Companions had stopped a few meters back. Now Raj felt Suzette's hand leave his; she sank down with a courtier's elegance, making the gesture of reverence seem a dance. He walked three more steps to the edge of the carpet and went to one knee, bowing his head deeply and putting a hand to his breast — the privilege of his rank, as a general and as one of Barholm's chosen Guards. It might have done him some good to have made the three prostrations of a supplicant; on the other hand, that could be taken as an admission of guilt.

You never know, with Barholm, Raj thought. You never know. Center?

Effect too uncertain to usefully calculate, the passionless inner voice said. After a pause: with Barholm even chaos theory is becoming of limited predictive ability.

Raj blinked. There were times he thought Center was developing a sense of humor. That was obscurely disturbing in its own right. Dark take it, he'd never been much good at pleading anyway. Flickers of holographic projection crossed his vision; Barholm calling the curse of the Spirit down on his head, Barholm pinning a high decoration to Raj's chest —

Cloth-of-gold robes sewn with emeralds and sapphires swirled into Raj's view. The toes of equally lavish slippers showed from under them. A tense silence filled the Hall; Raj could feel the eyes on his back, hundreds of them. Like a pack of carnosauroids waiting for a cow to stumble, he thought. Then:

"Rise, Raj Whitehall!"

Barholm's voice was a precision instrument, deep and mellow. With the superb acoustics of the hall behind it, the words rolled out more clearly than the Janitor's had through the megaphone. Behind them a long rustling sigh marked the release of tension.

Raj came to his feet, bending slightly for the ceremonial embrace and touch of cheeks. He was several centimeters taller than the Governor, although they were both Descotters. Barholm had the brick build and dark heavy features common there, but Raj's father had married a noblewoman from the far northwest, Kelden County. Folk there were nearly as tall and fair as the Namerique-speaking barbarians of the Military Governments.

The two men turned, the tall soldier and the stocky autocrat Barholm's hand rested on his general's shoulder, a mark of high favor. Behind them the bidden chorus sang a high wordless note.

"Nobles and clerics of the Civil Government — behold the man who We call Savior of the State! Behold the Sword of the Spirit of Man!" The orator's voice rolled out again. The chorus came crashing in on the heels of it:

"Praise him! Praise him! Praise him!"

Raj watched the throng come to their feet, putting one palm to their ears and raising the other hand to the sky — invoking the Spirit of Man of the Stars as they shouted, "Glory, glory!" and "You conquer, Barholm!"

Every one of them would have cheered his summary execution with equal enthusiasm — or greater.

Suzette's shining eyes met his.

Not quite all, Center reminded him. Behind Suzette the Companions were grinning as they cheered, far less than all.

The cheering died as Barholm raised a hand. "On Starday next shall be held a great day of rejoicing in the Temple and throughout the city. For three days thereafter East Residence shall hold festival in honor of General Whitehall and the brave men he led to victory over the barbarians of the Squadron; wine barrels shall stand at every crossroads, and the government storehouses will dispense to the people. On the third day, the spoils and prisoners will be exhibited in the Canidrome, to be followed by races and games in honor of the Savior of the State."

This time the cheers were deafening; if there was one thing everyone in East Residence loved, it was a spectacle. The chorus was barely audible, and the sound rose to a new peak as Barholm embraced Raj once more.

"There'll be a staff meeting right after all this play-acting," he said into Raj's ear, his voice flat. "There's the campaign in the Western Territories to plan."

He turned, and everyone bowed low as he withdrew through the private entrance behind the Chair.

So passes the glory of this world, Raj thought. Death or victory, and if victory —

Observe, Center said. Holographic vision shimmered before his eyes, invisible to any but himself:

It took a moment for Raj to recognize the naked man: it was himself, his face contorted and slick with the burnt fluid of his own eyeballs, after the irons had had their way with them. Thick leather straps held his wrists and ankles splayed out in an X.

The hooded executioners were just fastening each limb to the pull-chain of a yoke of oxen. The crowd beyond murmured, held back by a line of leveled bayonets.

Chapter Two

Governor Barholm stood while the servants stripped off his heavy robes. The Negrin Room dated to the reign of Negrin III, three centuries before; the walls were pale stone, traced over with delicate murals of reeds and flying dactosauroids and waterfowl; there was only one small Star, a token obeisance to religion as had been common in that impious age. The heads of the Ministries were there, and Mihwel Berg as Administrator of the newly-conquered Southern Territories and representative of the Administrative Service; Chancellor Tzetzas, of course; General Klostermann, Master of Soldiers, Bernardinho Rivadavia, the Minister of Barbarians, and Lady Anne Clerett as well, the Governors wife. She gave Raj a sincere smile as they waited for the Governor to finish disrobing.

There's one real friend at court, he thought. Suzette's friend, actually.

Barholm sat, and the others bowed and joined him.

"Well, messers," he said abruptly, opening the file an aide placed before him. "It's time to deal with the Western Territories and the barbarians of the Brigade who impiously hold the Old Residence, original seat of the Civil Government of Holy Federation — since we've reduced the Southern Territories quite satisfactorily, thanks to the aid of the Spirit of Man of the Stars, and Its Sword, General Whitehall."

There was a murmur of applause, and Raj looked down at his hands. "I had good troops and officers," he said.

"Your Supremacy," Tzetzas said. "We all give praise to the Spirit" — there was a mass touching of amulets, most of them genuine ancient computer components, in this assembly — "and to our General Whitehall, and to your wise policy, that the barbarian heretics were defeated so easily. Yet I would be remiss in my duties if I failed to point out that the Civil Government is still reeling from the expense of the southern campaign — completed less than a year ago. Which has, in fact, so far served to enrich only the officers involved in the operation."

Observe, Center said:

Muzzaf Kerpatik was on the docks in Port Murchison, capital of the reconquered Southern Territories. He was a small dark man from Komar, near the Colonial border; once a merchant and agent of Chancellor Tzetzas, until the latter's schemes had grown too much for even his elastic conscience. Since then he'd proven himself useful to Raj in a number of ways . . . although Raj hadn't known about this one, precisely. He was overseeing the loading of a ship, a medium-sized three-masted merchantman. Bolts of silk were going aboard, and burlap sacks filled with crystals of raw saltpeter, bales of rosauroid hides, and slatted wooden boxes stuffed with what looked like gold and silver tableware. A coffle of women chained neck-and-neck waited to board later: all young and good-looking, some stunningly so, and in the remnants of rich clothing in the gaudy style of the Squadron nobility — families of those barbarian nobles who'd refused to yield to the Spirit of Man of the Stars or missed the amnesty after the surrender, headed for Civil Government slave markets.

Raj thought he could place the time: about a month after the final battle on the docks. It had taken that long, and repeated scrubbings, before the rotting blood stopped drawing crawling mats of flies.

I'd heard about streets running with blood, he reminded himself. Never seen it until then. Vice-Admiral Curtis Auburn had landed ten thousand Squadron warriors on those docks, unaware that the main Squadron host was defeated and Raj in control of the city. Curtis had been lucky enough to be captured almost immediately, but less than one in ten of his men had survived the day.

The vision couldn't be much more than a month after that, because Suzette was riding up and leaning down to examine the checklist in Kerpatik's hand, and both Whitehalls had sailed home when Raj was recalled in quasi-disgrace.

"Should we not pause and recoup our resources?" the Chancellor concluded. "Especially when our internal situation is so delicate."

Due in no small measure to Your Most Blatant Corruptibility, Raj thought ironically. There was a popular East Residence legend that a poisonous fangmouth had once bitten Tzetzas at a garden party, the unfortunate reptile was believed to have died in horrible convulsions within minutes. The Chancellor had raised enormous sums for Barholm's wars and public works projects, and a good deal of it had stuck to his own beautifully manicured fingers.

Raj's expression was blandly respectful and attentive. On the expedition to the Southern Territories, Tzetzas had seen that Raj sailed with weevily hardtack and bunker coal that was half shale; Raj had returned the favor in his last stop in Civil Government territory by exchanging the goods for replacements from Tzetzas's own estates and mines, at full book price.

Observe, Center said,

Sesar Chayvez stood before his patron. The plump little man was sweating as Tzetzas sat leafing through the documents in the file before him.

"And here, my dear Sesar, we come to your signature, right next to that of then-Brigadier Whitehall and Mihwel Berg of the Administrative Service, on the bottom of this requisition order. Authorizing the exchange of worthless trash for goods from my estates in Kolobassa District."

His voice was light, even slightly amused. "An exchange which, since the hardtack in question was useful only for pig feed and the coal unsalable in an exporting center like Hayapalco, cost me approximately fourteen thousand gold FedCreds. Not to mention the expenses for repairing estates ruined when Whitehall quartered Skinner mercenaries on them to . . . shall we say, motivate the staff to cooperation."

"Your Most Excellent Honorability," Chayvez said, twining his fingers together.

His eyes flicked around the room, on the cabinets of well-thumbed books, the curios, the restrained elegance of the mosaic floor. Oddly, that was mostly covered with a square of waxed canvas on this visit. He swallowed and forced himself to continue:

"The . . . the hill-bandit of a Descotter occupied my headquarters with troops loyal only to him!" he burst out. "One of his thugs started to strangle me with a wire noose until I signed. What could I do?"

"Oh, I can understand your fears," Tzetzas said, waving a deprecatory hand. Chayvez began to relax. "In fact, it isn't the first time that Whitehall and those ruffian Companions of his have caused me substantial trouble. They brutalized a number of my placemen and employees in Komar, when stationed there. Brutalized them so thoroughly — I believe they began to skin one of them — that they revealed far, far too much, and I was forced to turn over all my investments in the province to the Chair to avoid serious disfavor."

Barholm had been quite annoyed. The scheme had involved holding up the landgrants usually given to infantry garrison troops, and then pocketing the revenues from the State farms. It might have gone unnoticed if Raj Whitehall hadn't been sent to bolster that particular frontier against the Colony.

Chayvez nodded enthusiastically. "The man is a menace to peace and orderly government, Your Most Excellent Honorability," he said.

"True. You will understand, then."

"Ah . . ." The plump provincial governor hesitated. "Understand, Your —"

"Yes, yes. That I cannot have my servants more afraid of Whitehall than of me. I believe his tame thug began to strangle you?"

A shadow moved from a corner of the darkened room. It grew into a man, a black man in a long dark robe. Not from one of the highly civilized city-states of Zanj; his tribal scars showed him to be from much farther south and west, from the savannahs of Majinga. The slave was nearly two meters tall, with shoulders like a bull moving beneath the cloth of his kanzu. His tongueless mouth gobbled in thick joy as he closed his fingers around the little man's neck and lifted him clear of the floor. Chayvez's arms and legs thrashed for a moment, beating at the boulder-solid form of the black and then twitching helplessly. The massive hands clamped tighter and tighter, closing by increments. When the neck snapped at last the bureaucrat had been still for several minutes. Urine and other fluids dripped to the waxed canvas on the floor.

"Wrap the body, and drop it in an alley," Tzetzas said, in a language quite unlike the Sponglish of civilization. The mute bowed silently and bent to his task as the Chancellor turned up the coal-oil lamp and took another file from the sauroid-ivory holder on his desk

Raj met Tzetzas's eyes and inclined his head. The Chancellor matched the gesture with one almost as imperceptible and far more graceful

Barholm explained to Raj: "There's been another outbreak of the anti-hardcopyist heresy down in Cerest. It's nothing serious; just a boil. When you've got a boil on your bum, you lance it and ignore it."

There were shocked murmurs; Raj touched his own amulet, a gold-chased chipboard fragment blessed by Saint Wu herself. "Wasn't that heresy anathematized two centuries ago?" he said.

"Yes, but it's like black plague, always breaking out again," the Governor said. "This time they're taking a new tack; calling circuit diagrams themselves 'false schematics' and corrupted data, not just denouncing allegorical representations. We can't afford trouble in Cerest —"

Raj nodded; a good deal of the capital's grain was shipped from there, and the Tarr Valley was the trade route to the rich tropical lands of the Zanj city-states. Or at least the only route that didn't run through the hostile Colony.

"— so I'm sending a brigade and a Viral Cleanser Sysup to purge their subroutines of heresy for good and all." He shook his square-jawed head; there was more silver in the black hair than Raj remembered. Being Governor was a high-stress occupation too.

Observe, Center said.

Blinding sunlight in the main square of Cerest, a prosperous-looking provincial capital. A domed Star Temple, with the many-rayed symbol atop it; the square bulk of a regional Prefect's palace across from it, fountains and arcades all about. A crowd filled most of the open paved space. It moaned as men — and a few women — were led out to a long row of iron posts set deep in the pavement. They shook their heads and refused the offered Headsets, symbolic connection to the Terminals of confession; two spat at the officiating priests. The soldiers hustled them on, supporting as much as forcing. Most of the prisoners' bare feet showed oozing sores where their toenails should have been.

The iron posts were joined in a complete loop by thick copper cables; the ends of the cables disappeared into a wagon-mounted box with an external flywheel belt—driven by the power take-off of a steam haulage engine. As the steel chains bound them to the posts, the prisoners began to sing, a hymn in some thick local dialect Raj couldn't follow. Out in the crowd others took it up, men in the rough brown robes of desert monks, women in the archaic jumpsuits and tunics of Renunciate Sisters, then the ragged dezpohblado crowd of town laborers. An officer barked an order and the troops blocking off the execution ground formed, the first rank dropping to one knee, both leveling their rifles.

The belt drive to the generator whined, and a hooded executioner put his hand on a scissor-switch. The Sysup in his gold-embroidered overrobe stood in the attitude of prayer — one hand over his ear, the other stretched up with its fingers making keying motions — and then swept it down. The man in the leather hood matched his gesture with a showman's timing, and blue sparks popped from the dangling cables. The prisoners stopped singing, but they could not scream with the DC current running through their bodies, only convulse against the iron poles.

A rock arched through the air and took one of the soldiers in the mouth. He collapsed backward limply; there was no motion from the others besides a ripple of movement as they closed ranks. They were Regulars, dragoons. . . .

More rocks flew. Raj could see the officer's lips move silently, in a prayer or curse. Then he shouted an order:

"Volley fire!" An endless line of white puffs, and the crowd recoiled, all but those smashed off their feet by the heavy bullets. The soldiers worked the levers of their rifles, reloaded. Another order, and they began to advance in a serried line, bayonets advanced.

Raj blinked. As always, the holographic vision lasted far less time than it seemed. Chancellor Tzetzas was steepling his fingers:

". . . necessary measures, true. Cerest Province is far too valuable to risk"

Especially with what our dear Chancellor makes from the chocolate, torofib and kave monopolies, Raj thought ironically. And I'll bet he fiddles on the share the fisc is supposed to get.

Probability 97% ±2%, Center said. However, total receipts to the fisc have increased while he holds the monopolies, due to volume growth.

"Still, undertaking another campaign at this time — when, as I mentioned, we have yet to recoup the expenses of the last, well . . ." There was a spare gesture of the long hand

Mihwel Berg, now Administrator of the Southern Territories, sniffed; he was a mousy little man, and watching him defy Tzetzas was like seeing a sheep turn on a carnosauroid. "Your Excellency, I might point out that all out-of-pocket expenses for the Expeditionary Force have already been recouped, with plunder, sale of prisoners, and other cash receipts alone leaving a surplus of no less than seven hundred fifty-four thousand FedCreds to the fisc. Gold."

Barholm sat straighter, casting a sidelong glance at his Chancellor. That was a considerable sum even by the Civil Governments standards. The Governor might be obsessed with reclaiming the territories lost to the Military Governments centuries ago, but he was keenly aware of financial matters.

"Furthermore, and even without the invaluable services which Your Excellency's tax-farming syndicates provide to the fisc, the first six months' revenues from the Southern Territories under Administrative Services control, annualized, are tenth out of the twenty-two Counties and Territories currently under effective Civil Government control.

"And," Berg went on, warming to his topic, "that does not include the revenues from estates confiscated from deceased or captured members of the Squadron — which amount to nearly half of the arable land in the district, if we include the one-third confiscation of Squadron nobles who surrendered before the collapse and, of course, the Admiral's own lands. Ex-Admiral, that is. That revenue alone will double the overall receipts from the Territories, and this is after we deduct lands to be deeded to peasant militia, infantry garrison plots, and estates to support the Church. Furthermore, the Territories have much untapped potential neglected under the Admirals. If our Sovereign Mighty Lord will examine the proposals —"

He slid a package of documents across the table; Barholm untied the ribbon and began riffling through them with interest. Tzetzas's fingers crooked like talons. The Chancellor usually had a say in what reached the Governor's desk, and he valued that power. Governor Barholm was a hard-working administrator, and an enthusiast for useful public works.

"— a railway to the saltpeter mines alone would increase the total yield of the Territories by fifteen percent" — saltpeter was a Chair monopoly, and the deposits south of Port Murchison were the richest in the known world — "besides making economical the copper and zinc deposits there, closed for three generations. There are also irrigation works to be brought back into operation, road repairs . . . Your Supremacy, launching the Expeditionary Force was the most lucrative stroke of policy any Governor has made in two hundred years."

Klosterman pulled at his muttonchop whiskers. "Still, even if the Colony is quiet, I'd not like to take too many troops away from the border," he said. The Master of Soldiers' last regional field command had been of Eastern Forces. "Ali's no fool, but he's vain, and he's vicious as a starving carnosauroid to boot."

Barholm shrugged. "He may have killed his brother Akbar, but they'll take a while to recover from their civil war."

Good fortune had given the Civil Government four strong Governors in a row, with no usurpations or civil conflicts — the primary reason for its current strength and unprecedented prosperity — but disputed successions were a problem both the Civil Government and the Colony were thoroughly familiar with.

Observe, Center said.

A one-eyed man stood among burned-out ruins. Raj recognized him instantly: Tewfik bin-Jamal, son of the late Settler of the Colony, and commander of all his armies. Raj had lost one minor battle to him, and won a major one by a thin margin; and every day in his prayers the general thanked the Spirit of Man for the Colonist superstition that made Tewfik ineligible for the Settler's throne because he lacked an eye.

The stocky, muscular body filled the regulation crimson djellaba with a solid authority, and the Seal of Solomon marked his eyepatch. Officers of the Colonial regulars and black-robed personal mamelukes followed the Muslim general as he stalked through the shattered building. He kicked at a frame of cindered boards; they slid away in ash that drifted ghostly under the bright sun, revealing the warped brass and iron shape of a lathe. Other machines stood amid the ruins, as did the cast-iron poles that had carried the drive shaft from a steam engine.

Tewfik's face was impassive beneath his spired spike-topped helmet, but the grip of his left hand on the plain wired brass hilt of his scimitar was white-knuckled with the effort of controlling his rage. The Colony armed its forces with lever-operated repeating carbines, and the machine shops that turned them out were a rare and precious asset. Now there was one less.

He turned; the viewpoint turned with him, staying behind his left shoulder. Beyond the fallen door-arch of the factory were more ruins, then intact buildings, and a long slope down to a great river. Flat roofs and minarets, smokestacks, towers glinting with colored tile, narrow twisting streets and irregular plazas around splashing fountains: Al Kebir, the capital of the Colony and the oldest city on Bellevue. Half a dozen huge bridges crossed the river, and the water was thronged with lateen-sailed dhows and sambuks, with barges and rafts and steamboats. Across the river was a burst of greenery, palms and jacaranda trees, and a great interlinked pile of low, ornately carved marble buildings taking up scores of hectares before the sprawl of the city resumed. An endless low rumble carried through the air, the sound of a million human beings and their doings, pierced through with the high wailing call of a muezzin.

The robed men sank to their knees in prayer; Tewfik waited an instant as his attendants spread a prayer rug before he bent his head towards the distant holy city of Sinnar, where the first ships to reach Bellevue had carried a fragment of the Kaaba from burning Mecca.

When he rose he turned to the man in a civilian outfit of baggy pantaloons, sash, turban and curl-toed slippers. At his fingers motion two of the mameluke slave-soldiers — one blond, one black, both huge men moving as lightly as cats — stood behind the civilian. The heavy curved swords in their hands rested lightly on his shoulders.

"Sa'id —" the man began.

Prince. That much Raj would have known, but as always Center somehow provided the knowledge that made the Arabic as understandable as his native Sponglish.

"Prince," the man went on, "what could we do? Your brother Akbar's followers came and demanded the finished arms; then the household troops of your brother Ali attacked them. We are not fighting men here."

Tewfik nodded, his hand stroking his beard. "Kismet," he said: fate. "When the kaphar, the infidels of the Civil Government, slew our father, it was Akbar's fate to reach for power and fail" — and leave his head on a pole before the Grand Mosque — "and yours to repair the damage as quickly as may be. If I thought you truly responsible, I would not threaten."

The manager nodded unconsciously; if Tewfik thought that the staff were dragging their feet, there would have been another set of heads on a pole some time ago.

"How long?" Tewfik asked, his voice like millstones of patience that would grind results out of time and fate by sheer force of will.

"If the Settler Ali, upon whom may Allah shower His blessings, advances the necessary funds, we will be turning out carbines again in six months," he said.

Tewfik's right hand rested on the butt of his revolver. One index finger gestured, and the mamelukes pressed the factory manager to his knees with the blunt back edges of their scimitars. The blades crossed before his neck, ready to scissor through it like a gardener's shears through the stem of a tulip.

"Six months!" the man cried; he ripped open his jacket to bare his breast in token of his willingness to die. "Prince Tewfik, we are adepts of the mechanic arts here, not dervishes or magicians! Machine tools cannot be flogged into obedience — six months and no more, but no less. May I be boiled alive and my children's flesh eaten by wild dogs if I lie!"

"That can be arranged . . . if you lie," Tewfik said somberly. The man met his eyes, ignoring the blades so near his flesh. The Colonist general sighed and signed the swordsmen back. There is no God but God, and all things are accomplished according to the will of God. In the name of the Merciful, the Lovingkind, I shall not make you bear the weight of an anger earned elsewhere. Come, my friend; rise, and we will speak of details over sherbet with my staff. Soon the Dar 'as-Salaam will need the weapons. There is a great stirring in the House of War."

Raj nodded. "Ali will wait; a year, maybe two if he has enough sense to listen to Tewfik.

"Still," he went on, "the Brigade's a more serious proposition than the Squadron was. They've been in contact with civilization longer, and they do have a standing army of sorts; plus they've some recent combat experience."

Mostly against the Stalwarts in the north; those were savages, but numerous, vicious and treacherous to a fault

"Also the Western Territories are bigger — not just in raw area, the population. Not so much desert. I'd say for a really thorough pacification . . . forty thousand troops. Fifteen thousand cavalry."

There were outraged screams around the table. "Out of the question!" Tzetzas barked, startled out of his usual suavity, and Barholm was looking narrow-eyed.

"That would be a little large," he said carefully. "Particularly as we're hoping that General Forker won't fight."

"Sovereign Mighty Lord, Forker may not fight but I doubt the Brigade will roll over that easily," Raj said.

"Fifteen thousand is about as much as we could spare," Barholm said, tapping a knuckle against the table to show that the question was closed. "That proved ample for the Squadron. Another battalion or two of cavalry, perhaps more guns."

The ruler leaned back. "Besides that," he went on, "General Forker —" the Brigades ruler kept the ancient title, although in the Western Territories it had come to mean king rather than a military rank "— is by no means necessarily hostile to the Civil Government. He spent better than a year negotiating for help while he was maneuvering to replace the late General Welf."

"He managed to do that without our aid, though, didn't he, Sovereign Mighty Lord?"

The Minister of Barbarians shuffled through his notes. "Yes, General Whitehall. In fact, he showed an almost, well, almost civilized subtlety during the negotiations. Then he married Charlotte Welf, the late General's widow. That made his election to the General's position inevitable. We were, I confess, surprised."

"Not as surprised as she was when he murdered her as soon as he was firmly in power," Barholm said, grinning; there was a polite chuckle.

Observe, Center said. A brief flicker this time; a woman in her bath. Handsome in a big-boned way, with grey in her long blond hair. She looked up angrily when the maidservant scrubbing her back fled, then tried to stand herself as she saw the big bearded men who had forced their way through the door. They wore bandanas over their lower faces, but the short fringed leather jackets marked them as Brigade nobles. Water fountained over the marble tiles of the bathroom as they gripped her head and held it under the surface. Her feet kicked free, thrashing at the water for a moment until the body slumped. Then there were only the warriors' arms, rigid bars down through the floating soapsuds. . . .

Chancellor Tzetzas raised an index finger in stylized horror. "Quite a gothic tale," he said. "Barbarians."

Raj nodded. "We can certainly spare seventeen or eighteen thousand men," he went on. "The Southern Territories are fairly quiet, all they need is garrison forces to keep the desert nomads in order. The military captives sent here will more than replace any drawdown. We could ship a substantial force into Stern Island —" that was directly north of the reconquered Southern Territories, and the easternmost Brigade possession "— and . . . hmm. Don't we have some claim to it, being heirs to the Admirals? It would make a first-rate base for an advance to the west"

The Minister of Barbarians leaned forward. "Indeed," he said, pushing up his glasses. "The former Admiral of the Squadron — ex-Admiral Auburn's predecessor's father — married Mindy-Sue Grakker, a daughter of the then General of the Brigade, and acquired extensive estates on Stern Island as her dower. The Brigade commander there has refused to turn over their administration to the envoys I sent."

"Excellent," Barholm said, leaning back and steepling his fingers. He might be of Descotter descent, but his fine-honed love of a good, legally sound swindle was that of a native-born East Residencer. "From there, we can exploit opportunity as it offers."

"Your Supremacy," Raj said in agreement. "We could move most of the troops up from the Southern Territories? They're surplus to requirements, closer, and I know what they can do. It's going on for summer already, so there's a time factor here."

"Ah," Barholm said, giving him a long, considering look. "Well, General, I'll certainly withdraw some of those forces . . . but it wouldn't be wise to make it appear that you have some sort of private army of your own. People might misunderstand. . . ."

Raj smiled politely. "Quite true, Your Supremacy," he said.

Everyone understands that it's the Army that disposes of the Chair, in the end. Three generations without a coup would be something of a record — if you didn't count Barholm's own uncle Vernier Clerett. He hadn't shot his way onto the Chair, strictly speaking, but he had been Commander of East Residence Forces when the last Poplanich Governor died of natural causes.

Probably natural causes.

"We certainly don't want people to think that," Raj went on. "Half the cavalry battalions from the Southern Territories, then?" Barholm nodded.

"And the infantry?"

"By all means," the Governor said, slightly surprised Raj would mention the subject Infantry were second-line troops, and Barholm saw little difference between one battalion of them and another.

You haven't seen what Jorg Menyez and I can do with them, Raj thought. "I'll draw the other cavalry battalions and artillery from the Residence Area Forces Group, then?"

Barholm signed assent "I'll be sending along my nephew Cabot Clerett, as well," the Governor said. "He's been promoted to Major, in command of the 1st Residence Battalion." A Life Guards unit; they rarely left East Residence, but many of the men were veterans from other outfits. Of late, most had been from the Clerett family's estates. "It's time Cabot got some military experience."

Raj spread his hands. "At your command, Your Supremacy. I've met him; he seems an intelligent young officer, and doubtless brave as well." A subtle reminder: don't blame me if he stops a bullet somewhere.

"Indeed. Although I hope he won't be seeing too much action." An equally subtle hint: he's my heir. Barholm was nearly forty, and he and Lady Anne hadn't produced a child in fifteen years of marriage. The Governor smiled like a shark at the exchange. It was worth the risk, since he had other nephews. A Governor didn't have to be a general, but he did need enough field experience for fighting men to respect him. He continued:

"In fact — this doesn't go beyond these walls — we are, in fact, negotiating with General Forker right now. The, ah, death of Charlotte Welf . . . Charlotte Forker . . . aroused considerable animosity among some of the Brigade nobles. Particularly since Forker's main claim to membership in the Amalson family was through her. General Forker has expressed interest in our offer of a substantial annuity and an estate near East Residence in return for his abdication in favor of the Civil Government."

"He may abdicate, Sovereign Mighty Lord, but I doubt his nobles would all go along with it. The Brigade monarchy is elective within the House of Theodore Amalson. The Military Council includes all the adult males, and they can depose him and put someone else in his place."

"That," Barholm said dryly, "is why we're sending an army."

Raj nodded "I'll get right on to it, then, Your Supremacy, as soon as the Gubernatorial Receipt —" a general-purpose authorizing order "— comes through. It'll take a month or so to coordinate . . . by your leave, Sovereign Mighty Lord?"

Chapter Three

How utterly foolish of him, Suzette Whitehall thought, looking at the petitioner.

Lady Anne leaned her head on one hand, her elbow on the satinwood arm of her chair. Her levees were much simpler than the Governor's, as befitted a Consort. Apart from the Life Guard troopers by the door, only a few of her ladies-in-waiting were present, and the room was lavish but not very large. A pleasant scent of flowers came through the open windows, and the sound of a gitar being strummed. The cool spring breeze fluttered the dappled silk hangings.

Despite that, the Illustrious Deyago Rihvera was sweating. He was a plump little man whose stomach strained at the limits of his embroidered vest and high-collared tailcoat, and his hand kept coming up to fiddle with the emerald stickpin in his lace cravat

Suzette reflected that he probably just did not connect the glorious Lady Anne Clerett with Supple Annie, the child-acrobat, actress and courtesan. He'd only been a client of hers once or twice, from what Suzette had heard — even then, Anne had been choosey when she could. But since then Rihvera had been an associate of Tzetzas, and everyone knew how much the Consort hated the Chancellor. To be sure, the men who owed Rihvera the money he needed so desperately — to pay for his artistic pretensions — were under Anne's patronage. Not much use pursuing the claims in ordinary court while she protected them.

". . . and so you see, most glorious Lady, I petition only for simple justice," he concluded, mopping his face.

"Illustrious Rihvera —" Anne began.

A chorus broke in from behind the silk curtains. They were softer-voiced, but otherwise an eerie reproduction of the Audience Hall singers, castrati and young girls:

"Thou art flatulent, Oh Illustrious Deyago Pot-bellied, too:

Oh incessantly farting, pot-bellied one!"

Silver hand-bells rang a sweet counterpoint. Anne sat up straighter and looked around.

"Did you hear anything?" she murmured.

Suzette cleared her throat "Not a thing, glorious Lady. There's an unpleasant smell, though."

"Send for incense," the Consort said. Turning back to Rihvera, her expression serious. "Now, Illustrious —"

"You have a toad's mouth, Oh Illustrious Deyago — Bug eyes, too:

Oh toad-mouthed, bug-eyed one!"

This time the silver bells were accompanied by several realistic croaking sounds.

I wonder how long he can take it? Suzette thought, slowly waving her fan.

His hands were trembling as he began again.

"Are you well, my dear?" Suzette asked anxiously, when the petitioners and attendants were gone.

"It's nothing," Anne Clerett said briskly. "A bit of a grippe."

The Governor's lady looked a little thinner than usual, and worn now that the amusement had died away from her face. She was a tall woman, who wore her own long dark-red hair wound with pearls in defiance of Court fashion and protocol. For the rest she wore the tiara and jewelled bodice, flounced silk split skirt, leggings and slippers as if she had been born to them. Instead of working her way up from acrobat and child-whore down by the Camidrome and the Circus . . .

Suzette took off her own blond wig and let the spring breeze through the tall doors riffle her sweat-dampened black hair. It carried scents of greenery and flowers from the courtyard and the Palace gardens, with an undertaste of smoke from the city beyond.

"Thank you," she said to Anne. There was no need to specify, between them.

Anne Clerett shrugged. "It's nothing," she said. "I advise Barholm for his own good — and putting Raj in charge is the best move." She hesitated: "I realize my husband can be . . . difficult, at times."

He can be hysterical, Suzette thought coldly as she smiled and patted Anne's hand. In a raving funk back during the Victory Riots, when the city factions tried to throw out the Cleretts, Anne had told him to run if he wanted to, that she'd stay and burn the Palace around her rather than go back to the docks. That had put some backbone into him, that and Raj taking command of the Guards and putting down the riots with volley-fire and grapeshot and bayonet charges to clear the barricades.

He can also be a paranoid menace. Barholm was the finest administrator to sit the Chair in generations, and a demon for work — but he suspected everyone except Anne. Nor had he ever been much of a fighting man, and his jealousy of Raj was poisoning what was left of his good sense on the subject. A Governor was theoretically quasi-divine, with power of life and death over his subjects. In practice he held that power until he used it too often on too many influential subjects, enough to frighten the rest into killing him despite the dangerous uncertainty that always followed a coup. Barholm hadn't come anywhere near that.

Yet.

"Besides," Anne went on, "I stand by my friends."

Which was true. When Anne was merely the tart old Governor Vernier Clerett's nephew had unaccountably married, the other Messas of the Palace had barely noticed her. Except in the way they might have scraped something nasty off their shoes. Suzette had had better sense than those more conventional gentlewomen. Or perhaps just less snobbery, she thought. Her family was as ancient as any in the City; they had been nobles when the Cleretts and Whitehalls were minor bandit chiefs in the Descott hills. They had also been quite thoroughly poor by the time she came of age, years before she met Raj. The last few farms had been mortgaged to buy the gowns and jewels she needed to appear at Court

"You'll be accompanying Raj again?" Anne asked.

"Always," Suzette replied.

Anne nodded. "We both," she said, "have able husbands. But even the most able of men —"

"— needs help," Suzette replied. The Governor's Lady raised a fingertip and servants appeared with cigarettes in holders of carved sauroid ivory.

"I may need help with young Cabot," Suzette said. "He hasn't been much at Court?"

"Mostly back in Descott," Anne said "Keeping the Barholm name warm on the ancestral estates."

Which were meagre things in themselves. Descott was remote, a month's journey on dogback east and north of the capital, a poor upland County of volcanic plateaus and badlands. Mostly grazing country, with few products beyond wool, riding dogs and ornamental stone. Its other export was fighting men, proud poor backland squires and their followings of tough vakaros and yeoman-tenant ranchers, men born to the rifle and saddle, to the hunt and the blood feud. Utterly unlike the tax-broken peons of the central provinces. Only a fraction of the Civil Government's people lived there, but one in five of the elite mounted dragoons were Descotters. Most of the rest came from similar frontier areas, or were mercenaries from the barbaricum.

It was no accident that Descotters had held the Chair so often of late, nor that the Cleretts were anxious to keep first-hand ties with the clannish County gentry.

"Seriously, my dear," Anne went on, "you should look after young Clerett. He's . . . well, he's been champing at the bridle of late. Twenty, and a head full of romantic yeast and old stories. Quite likely to get himself killed — which would be a disaster. Barholm, ah, is quite attached to him."

The two women exchanged a look; both childless, both without illusion. It said a great deal for Anne that Barholm had not put her aside for not giving him an heir of his body, which was sufficient cause for divorce under Civil Government law.

"I'll try to see he comes back, Anne," Suzette said. If possible, she added to herself with clinical detachment. Romantic, ambitious young noblemen were not difficult to control; she had found that out long before her marriage. They could also be trouble when serious business was in question, such as the welfare of one's husband.

"I'm sure you can handle Cabot," Anne said. That sort of manipulation was skill they shared, in their somewhat different contexts.

"Poplanich needn't come back," Anne went on.

She smiled; Suzette looked away with a well-concealed shudder. A strayed ox might have noticed an expression like that on the last carnosauroid it ever saw.

Anne clapped her hands. "Thom Poplanich, Des Poplanich — Ehwardo would make a beautiful matched set, don't you think?" And it would leave the Poplanich gens without an adult male of note. Thom's grandsire had been a well-loved Governor.

"Des was a rebel," Suzette said carefully. "I've never known what happened to Thom. Ehwardo is a loyal officer."

"Of course, of course," Anne said, chuckling and giving Suzette's hand a squeeze.

Raj's wife chuckled herself. There's irony for you, she thought: I really don't know what happened to Thom.

Raj simply refused to discuss it, and he had been different ever since he came back from the tunnels they'd gone exploring in; the ground under East Residence was honeycombed with them. Suzette might have advised quietly braining Thom Poplanich and leaving him in the catacombs, as a career move and personal insurance — except that she knew that Raj would never have considered it. He had changed, but not like that.

You are too good for this Fallen world, my angel, she thought toward the absent Raj. It is not made for so honorable a knight.

Then Lady Clerett's mouth twisted; she covered it with her palms and coughed rackingly.

"Anne!" Suzette cried, rising.

"It's nothing," she said, biting her lip. "Go on; you'll have a lot to do. Just a cough, it'll pass off with the spring. I'll deal with it."

There was blood on her fingers, hidden imperfectly by their fierce clench. Suzette made the minimal bow and withdrew.

"At the narrow passage there is no brother, no friend," she quoted softly to herself. And no allies against some enemies.

"So, what do we get?" Colonel Grammeck Dinnalsyn said; the artillery specialist had seen to his beloved 75mm field-guns, and was ready to take an interest in the less technical side of the next Expeditionary Force.

Raj and the other officers were riding side-by-side down the Main Street of the training base, in the peninsula foothills west of East Residence.

"5th Descott Guards, 7th Descott Rangers, 1st Rogor Slashers, 18th Komar Borderers, 21st Novy Haifa Dragoons, and Poplanich's Own from the cavalry in the Southern Territories. And all the infantry and guns."

"Jorg will be glad to get out of the Territories. Spirit knows I went and Entered my thanks when I got the movement orders for home. Not much happening there now, except that idiot they sent to replace you giving damn-fool orders."

"I'm glad we're getting Jorg. Nobody else I know can handle infantry like Menyez."

Most commanders didn't even try; infantry were used mainly for line-of-communication and garrison work in the Civil Government's army. Jorg had had his own 17th Kelden Foot and the 24th Valencia under his eye since Sandoral, nearly four years ago. Raj and he had done a fair bit with the other infantry battalions during the Southern Territories campaign, and Menyez had been working them hard in the year since.

"Then for the rest of the cavalry, the 1st and 2nd Residence Battalions, the Maximilliano Dragoons, and the the 1st and 2nd Mounted Cruisers from here." The artillery specialist raised an eyebrow at the last two units.

"Yes, they're Squadrones — but coming along nicely. Full of fight, too — for some reason they don't seem to resent our beating the scramento out of them. Quite the contrary, if anything. Eager to learn from us."

Observe, Center said:

"Right, ye horrible buggers," the sergeant said. "Who's next?"

He spun the rifle in his hands into a blurring circle; the bayonet was fixed, but with the sheath wired on to the blade. The three big men lying wheezing or moaning on the ground before the stocky Descotter had been holding similar weapons. The company behind them were standing at ease in double line with their rifles sloped. None of them looked very enthusiastic about serving as an object lesson. . . .

"Ten-'hut!" the sergeant said. The men were stripped to their baggy maroon pants, web-belts and boots; he was wearing in addition the blue sash, sleeveless grey cotton shirt and the orange-black checked neckerchief of the 5th Descott. "Now, we'uns will learn how to use the fukkin' baynit, won't we?"

"YES SERGEANT!" they screamed.

"Right. Now, yer feints to the eyes loik this, then gits 'em in t'belly loik this. Baynit forrard! An' one an' two —"

"Eager to learn from you, sir, actually," the artilleryman said. He was a slim man of medium height, with cropped black hair and black eyes and pale skin, and a clipped East Residence accent.

"It soothes their pride," he went on. "They call you an Avatar of the Spirit. And what man needs to be ashamed of yielding to the Spirit Incarnate? Not that I'd dispute you the title myself."

Raj frowned, touching his amulet. Dinnalsyn's casual blasphemy was natural enough for a man born in the City, but Raj had been raised in the old style back home on Hillchapel. A soldier of the Civil Government was also a warrior of the Spirit.

The ex-squadron personnel are undergoing transference, Center said, a common psychological phenomenon, and technically, you are an avatar.

"Speak of the Starless," Dinnalsyn noted.

He and Raj turned their dogs aside as a battalion came down the camp street toward them. First the standard-bearer, the long pole socketed to a ring in his right stirrup; the colors were furled in a tubular leather casing. Then the trumpeters and drummers, four of them. The battalion commander and his aides in a clump with the Senior Sergeant of the unit; then the six hundred and fifty men in column-of-fours, each man an exact three meters from the stirrups of his squadmates on either side, half a length from the dog before and behind. Triple gaps between companies, the company pennant, signaler and commander in each. An Armory rifle in a scabbard before each right knee, and a long slightly-curved saber strapped to the saddle on the other side.

The men wore round bowl-helmets with neckguards of chainmail-covered leather, dark-blue swallowtail coats, baggy maroon pants tucked into knee boots. Their mounts were farmbreds, Alsatians and Ridgebacks for the most part, running to a thousand pounds weight and fifteen hands at the shoulder. Everything regulation and by the handbooks, all the more startling because the men wearing the Civil Government uniforms were not the usual sort. The predominant physical type near East Residence was short, slight, olive to light-brown of skin, with dark hair and eyes. There were regional variations; Descotters tended to be darker than the norm, square-faced and built with barrel-chested solidity, while men from Kelden County were taller and fairer. The troops riding toward Raj and his companion were something else again. Big men, most near Raj's own 190 centimeters, and bearded in contrast to local custom; fair-skinned despite their weathered tans, many with blond or light-brown hair.

The massed thudding of paws and the occasional whine or growl was the only sound until a sharp order rang out

"2nd Mounted Cruisers — eyes right. General salute!"

A long rippling snap followed, each man's head turning sharply and fist coming to breast as they passed Raj. Raj returned the gesture. It was still something of a shock to see the barbarian faces in Army uniform. Even more shocking to remember the Squadron host as it tumbled toward the line of Civil Government troops; individual champions running out ahead to roar defiance, shapeless clots around the standards of the nobles, dust and movement and a vast, shambling chaos . . .

The ones who couldn't learn mostly died, he thought.

The battalion commander fell out and reined in beside them as the column passed in a pounding of pads on gravel and a jingle of harness.

"Bwenya dai, seyhor!" Ludwig Bellamy said.

He's changed too, Raj thought, offering his hand after the salute. Karl Bellamy had surrendered early to the Expeditionary Force, to preserve his estates and because he hated the Auburns who'd usurped rule of the Squadron. His eldest son had gone considerably further; the chin was bare, and his yellow hair was cut bowl-fashion in the manner of Descotter officers. His Sponglish had always been good in a classical East Residence way — tutors in childhood — but now it had caught just a hint of County rasp, the way a man of the Messer class from Descott would speak. Much like Raj's own, in fact. The lower part of the Squadron noble's face was still untanned, making him look a little younger than his twenty-three years.

"Movement orders?" he said eagerly. "I'm taking them out —" he tossed his head in the direction of his troops "— on a field problem, but we could —"

"No es so hurai," Raj said, fighting back a grin: not so fast. He had been a young, eager battalion commander himself, once. "But yes, we're moving. Stern Isle, first. You'll get a chance to show your men can remember their lessons in action."

"They will," Bellamy said flatly. Some of the animation died out of his face. "They remember — they know courage alone isn't enough."

They should, Raj thought.

Their families had been settled by military tenure on State lands as well, which meant their homes were here too.

"And they're eager to prove themselves."

Raj nodded; they would be. Back in the Southern Territories, they'd been members of the ruling classes, the descendants of conquerors. Proud men, anxious to earn back their pride as warriors.

I just hope they remember they're soldiers, now, Raj thought. Putting a Squadrone noble in command had been something of a risk; he'd transferred a Companion named Tejan M'Brust from the 5th Descott to command the 1st Cruisers. So far the gamble with the 2nd seemed to be paying off.

Aloud: "Speaking of education, Ludwig, I've got a little job for you, to occupy the munificent spare time a battalion commander enjoys. We'll be having a young man by the name of Cabot along."

The fair brows rose in silent enquiry.

"Cabot Clerett. I'd like —"

Chapter Four

The longboat's keel grounded on the beach, grating through the coarse sand. Sailors leaped overside into water waist-deep, heaving their shoulders against the planks of its hull. Raj vaulted to the sand, ignoring the water that seethed around his ankles, and swept his wife up in his arms to carry her beyond the high-tide mark. Miniluna and Maxiluna were both up, leaving a ghostly gloaming almost bright enough to read by even as the sun slipped below the horizon.

Offshore on a sea colored dark purple with sunset the fleet raised spars and sails tinted crimson by the dying light. Three-masted merchantmen for the most part, with a squadron of six paddle-wheel steam warships patrolling offshore like low-slung wolves. Not that there was much to fear; unlike the Squadron, who had been notable pirates, the Brigade didn't have much of a navy. Some of the smaller transports had been beached to unload their cargo; the rest were offloading into skiffs and rowboats. Except for the dogs. The half-ton animals were simply being pushed off the sides, usually with a muzzle on and fifteen or twenty men doing the pushing. Mournful howls rang across the water; once they were in, the intelligent beasts followed their masters' boats to shore. A few who'd been on the expedition against the Squadron jumped in on their own.

As Horace did; the big black hound shook himself, spattering Raj and Suzette equally, flopped down on the sand, put his head on his paws and went to sleep. Raj laughed; so did Suzette, close to his ear. He jumped when she ran her tongue into it briefly.

"When you start ignoring me even when I'm in your arms, my sweet . . ." she said playfully.

He walked a few steps further and set her down. In linen riding clothes, with a Colonial-made repeating carbine across her back, Suzette Whitehall did not look much like a Court lady of East Residence. But she looked very good to Raj, very good indeed.

"To work," he said.

The camp was already fully set up, a square half a kilometer on a side and ringed with ditch and earth embankment, and a palisaded firing-step on top. Within was a regular network of dirt lanes, flanked by the leather tents of the eight-man squads which were the basic unit of the Civil Government's armies. Broader lanes separated battalions, each with its Officers Row and shrine-tent for the unit standards. The two main north-south and east-west roadways met in the center at a broad open plaza, and in the center of that was a local landowners house that would be the commanders quarters. Dog-lines to the east, thunderous with barking as the evening mash was served; artillery park to the west; stores piled up mountainously under tarpaulins . . .

"Nicely done," he said And exactly where we camped the last time, he thought, with a complex of emotions.

A tall rangy man with a moustache pulled up — on a riding steer, an unusual choice of mount. Especially for a man with a Colonel's eighteen-rayed gold and silver star on his helmet and shoulder-patches. The inflamed rims around his eyes told why; he was violently allergic to dogs. A misfortune for a nobleman, disastrous for a nobleman set on a military career. Unless one was willing to settle for the despised infantry, of course. Probably a source of anguish to the man, but extremely convenient to Raj Whitehall. Usually the infantry got the dregs of the officer corps, men without either the connections or the ability to make a career in the mounted units.

"Nicely done, Jorg," Raj repeated, as the man swung down.

Jorg Menyez shrugged. "We've had three days, and I haven't wasted the time we spent stuck down there around Port Murchison," he said. They saluted and exchanged the embhrazo. "Spirit of Man but I'm glad to be out of the Territories! Nineteen battalions of infantry, five of cavalry, thirty guns, reporting as ordered, seyhor! And campgrounds, food, fodder and firewood for five more battalions of mounted troops." He bowed over Suzette's hand. "Enchanted, Messa."

"Excellent," Raj said again. It was damned good to have subordinates you could rely on to get their job done without hand-holding. That had taken years.

Indeed, Center said.

"All the old kompaydres together again, eh?" Jorg went on, as Gerrin Staenbridge came up. His eyes widened slightly as Ludwig Bellamy joined them, dripping.

"Sinkhole," the ex-member of the Squadron said, and sneezed.

"Make that sixty field guns, now," Grammek Dinnalsyn noted. "We brought another thirty, and some mortars. They may be useful."

"Staff meeting at dinner," Raj said. He toed Horace in the flank. "Up, you son of a bitch."

The hound sighed, yawned and stretched before rising.